Thoughts unsaid, then

forgotten

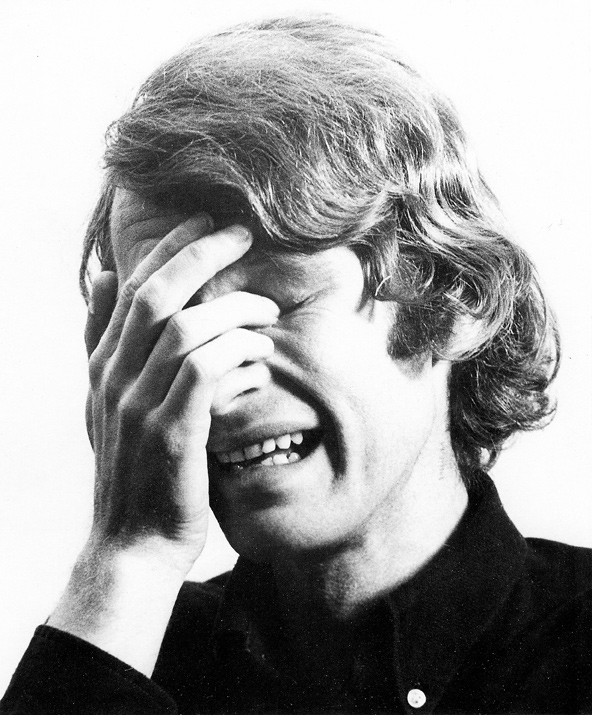

I’m Too Sad to Tell You is a mixed media artwork by conceptual artist Bas Jan Ader.

![]()

The work includes a three-minute black-and-white silent film, still photographs and a post card all related to him crying for an unknown reason. The photographs include both a short hair version and a long hair version. The post cards were mailed to his friends with the inscription “I'm too sad to tell you.”

The work includes a three-minute black-and-white silent film, still photographs and a post card all related to him crying for an unknown reason. The photographs include both a short hair version and a long hair version. The post cards were mailed to his friends with the inscription “I'm too sad to tell you.”

Influence

The work has influenced a large number of artists, with many composing interpretations and homages to the work. These include:

Alexander Brandt on his goal of imitating Ader’s pose in his own self portrait:

David Horvitz on the influence for his book “Sad Depressed People”:

Vik Muniz created “Self Portrait (I Am Too Sad to Tell You, after Bas Jan Ader)” with his head in his hand per Ader.

Hugh O’Donnell created a performance piece performed with Ader’s movie.

Lisa Rovner said Ader’s movie “was the most beautiful thing she’s ever seen.”

The work has influenced a large number of artists, with many composing interpretations and homages to the work. These include:

Alexander Brandt on his goal of imitating Ader’s pose in his own self portrait:

My appropriation of this visual has a strategic aim. I myself do not fit the cliché of a tragic artist.... It is the reactions it will produce with the audience that interest me.

David Horvitz on the influence for his book “Sad Depressed People”:

If you look at my book, all the images are with people’s hands to their faces...this was actually a direct reference to Ader’s image.

Vik Muniz created “Self Portrait (I Am Too Sad to Tell You, after Bas Jan Ader)” with his head in his hand per Ader.

Hugh O’Donnell created a performance piece performed with Ader’s movie.

Lisa Rovner said Ader’s movie “was the most beautiful thing she’s ever seen.”

The work’s original form was a silent black and white movie shot outdoors in 1970 apparently in front of Ader’s house. The movie was shown in Claremont College, but has since been lost.

A still from the movie, however, was extracted and made into a post card. It shows Ader with his head in his hand crying. The back of the post card had the written inscription “I'm too sad to tell you.” It was dated September 13, 1970.

The card was mailed to a number of Ader’s friends. The image has also been reproduced in a photographic version with the inscription written in the lower right hand corner. The post card and photograph have become iconic of the work and a symbol that many artists have emulated.

![]()

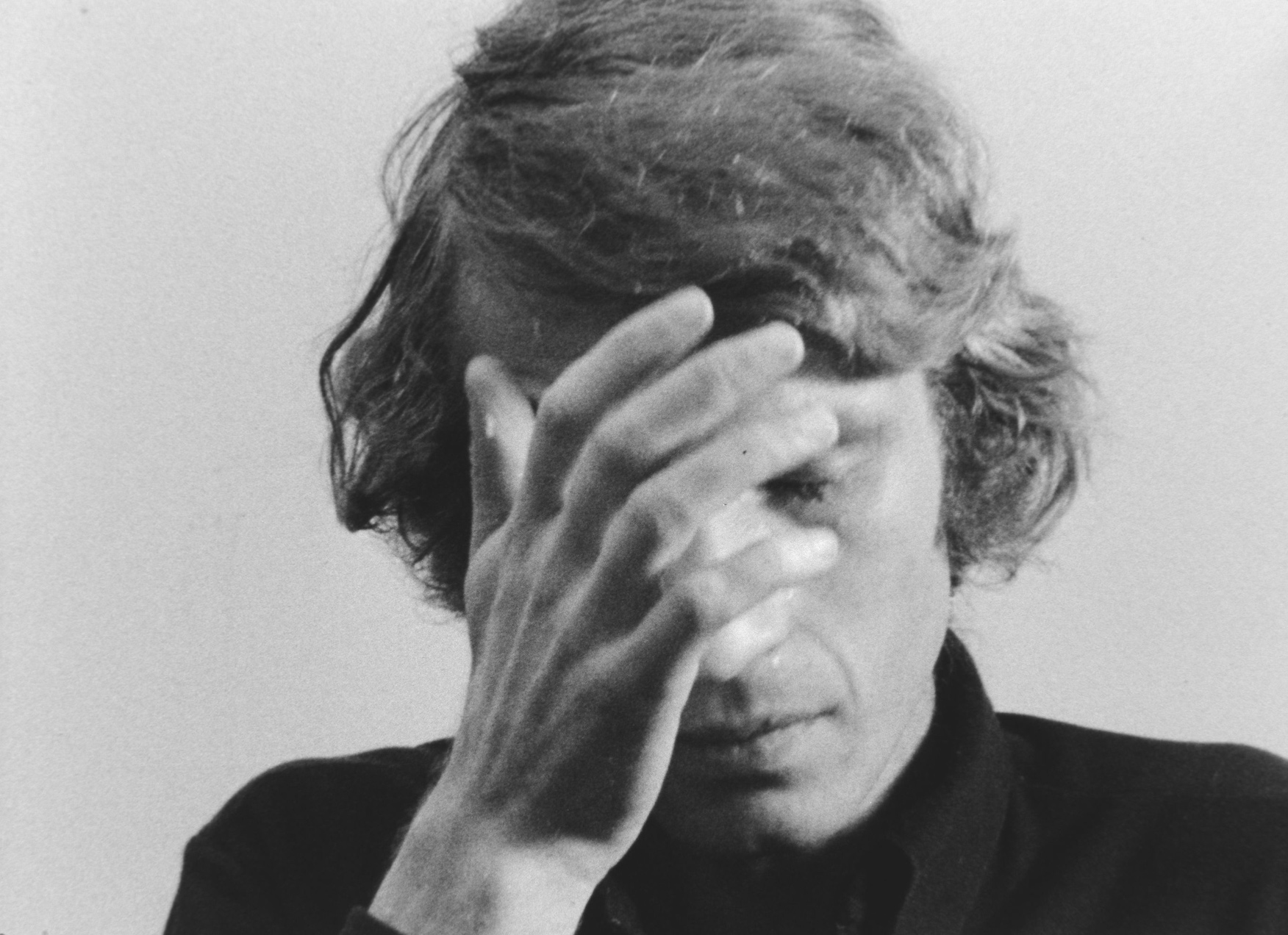

A second version of the film was made in Amsterdam in 1971. This was more of a performance with Ader appearing to be calm before the shooting and rubbing his eyes during the filming to produce tears and build emotional intensity.

Ten minutes of film was shot with the final version edited to about three and a half minutes.

The edited version captures Ader at his most anguished. His face is framed closely. There is no introduction or conclusion, no reason given and no relief from the anguish that is presented.

![]()

A still from the movie, however, was extracted and made into a post card. It shows Ader with his head in his hand crying. The back of the post card had the written inscription “I'm too sad to tell you.” It was dated September 13, 1970.

The card was mailed to a number of Ader’s friends. The image has also been reproduced in a photographic version with the inscription written in the lower right hand corner. The post card and photograph have become iconic of the work and a symbol that many artists have emulated.

A second version of the film was made in Amsterdam in 1971. This was more of a performance with Ader appearing to be calm before the shooting and rubbing his eyes during the filming to produce tears and build emotional intensity.

Ten minutes of film was shot with the final version edited to about three and a half minutes.

The edited version captures Ader at his most anguished. His face is framed closely. There is no introduction or conclusion, no reason given and no relief from the anguish that is presented.

Critics have said that it is hard not to be affected by the film, with its offering of “raw passion to anyone willing to watch.”

The work has inspired many critical interpretations and analyses.

![]()

There seems to be an overall tension between the sincerity of the artist’s captured emotions and performance aspects of the works.

Artists James Roberts and Collier Schorr, for example, feel the works are at once intensely personal and yet very arbitrary. There was a true reason for Ader’s sadness, but that is not shared with us.

Bruce Hainley, contributing editor to Artforum, thinks the reasons for his sadness are beside the point. In his view, Ader walks a fine line between sincerity (the sadness is real) and melodrama (the work is staged multiple times).

![]()

Jörg Heiser, coeditor of Frieze magazine, views the work as an ironic statement of the artist taking on all of the embarrassment of the expressed emotion while leaving it open as to whether or not the viewer takes on the embarrassment as well.

Women reviewers have been more critical.

Jennifer Doyle in her book “Hold it Against Me: Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art” feels the work may be seen as real due to the tradition of the “melancholy white male artist.”

Critical Interpretation

There seems to be an overall tension between the sincerity of the artist’s captured emotions and performance aspects of the works.

Artists James Roberts and Collier Schorr, for example, feel the works are at once intensely personal and yet very arbitrary. There was a true reason for Ader’s sadness, but that is not shared with us.

Bruce Hainley, contributing editor to Artforum, thinks the reasons for his sadness are beside the point. In his view, Ader walks a fine line between sincerity (the sadness is real) and melodrama (the work is staged multiple times).

Jörg Heiser, coeditor of Frieze magazine, views the work as an ironic statement of the artist taking on all of the embarrassment of the expressed emotion while leaving it open as to whether or not the viewer takes on the embarrassment as well.

Women reviewers have been more critical.

Jennifer Doyle in her book “Hold it Against Me: Difficulty and Emotion in Contemporary Art” feels the work may be seen as real due to the tradition of the “melancholy white male artist.”